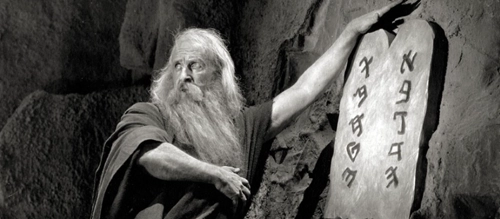

The Ten Commandments (1923)

Director: Cecil B. DeMille

Screenwriter: Jeanie Macpherson

Starring: Theodore Roberts, Leatrice Joy, Richard Dix, Rod LaRocque, Nita Naldi

It is impossible to watch the first 45 minutes of Cecil B. DeMille’s 1923 silent epic The Ten Commandments without your mouth hanging open in awe. The sheer artistry on display is astounding, from the art direction, to the cinematography, to the technical effects. Helmed by one of cinema’s most successful and influential pioneer directors, The Ten Commandments offers the very best of what movies can be, and 100 years later stands as a testament to the innovation and technical achievement of the early days of moving pictures, a reminder of the shoulders that artists today stand upon. According to The Film Foundation, it was Paramount’s highest-grossing film for 25 years. While DeMille’s 1956 remake of the film starring Charlton Heston and Yul Brynner is probably the version best remembered by audiences, thanks in part to ABC’s yearly tradition of airing the film the week before Easter, the original 1923 version is just as spectacular and worthy of praise and appreciation. At times bewildering and heavy-handed, The Ten Commandments is a sprawling morality tale that often loses the plot, but nevertheless offers us a fascinating glimpse into the primitive days of filmmaking, as well as the ideals and expectations of post-war America.

The Ten Commandments begins with a title card that explains how the modern world considered the laws of God to be “old fashioned,” but following the bloodshed of the first world war, that same world, now bitter and broken by death and destruction, “cries for a way out.” What follows is a 45 minute prologue retelling the Exodus from the first testament of the Bible, in which Moses (Theodore Roberts) leads thousands of enslaved Israelis from Egypt. But when the Pharaoh’s son cannot be revived by his Gods, Ramses (Charles De Roche) chases after them. Moses parts the Red Sea, goes to the Mount to receive the ten commandments and inflicts the wrath of God upon the Israelis when he returns, because they have forsaken God while Moses was away and are now worshipping a golden ram. The sinners pay for their disobedience; they are struck down by lightening.

Fans of the 1956 version might be a little bit confused about what happens next.

As the frame fades to black, the film jumps ahead to modern day, where the devoutly religious Martha McTavish (Edythe Chapman) is telling the story of “The Ten Commandments” to her two sons, John (Richard Dix) and Dan (Rod La Rocque). While John is a lowly carpenter and content to remain so, Dan has big plans for his future; plans that do not include respecting the teachings of God, much to the horror of his mother. Dan and John soon fall in love with the same girl, Mary (Leatrice Joy), which sparks a chain of events that lead to a deadly conclusion.

This last half of the film is a morality play about the dangers of falling from God’s grace, which the film never lets you forget. The dialog is so over the top it borders on self-parody. It’s way too on the nose and beats you over the head with its message. It’s hard not to laugh when Martha, horrified that Mary and Dan are listening to music and dancing on Sunday, dramatically smashes the record against her giant bible. As Shawn Hall pointed out in The Everyday Cinephile, “The choices of the characters are dictated by the morals the filmmakers are trying to teach the audience, not their inner motivations and desires.” Modern audiences, who are overwhelming less religiously minded than they were 100 years ago, might have a difficult time swallowing the film’s black and white morality, but this part of the film didn’t fare very well with audiences at the time of its release either, who saw it as a downgrade from the breadth and scope of the prologue. According the The Film Foundation, Variety at the time called it simply “ordinary.”

There’s a reason why, in DeMille’s 1956 remake, the Exodus and parting of the red sea serves as the climax of the story. It’s the most exciting part. Starting the 1923 version with this sequence, DeMille set his audience up for disappointment. There’s just no matching its insane spectacle and technical prowess. According to The Film Foundation, the sets for the prologue were built by 500 carpenters and 600 painters and decorators. The sets, including a 120 feet tall temple, were massive. This was a hugely expensive production, and it still looks expensive after all these years. It’s also worth noting that several scenes in the prologue were in color, including the parting of the red sea and the fire used to hold back the Egyptian chariot riders. According to The Musuem of Modern Art, DeMille used several techniques for adding color during the silent era including tinting, spot-coloring and techicolor. If anything, The Ten Commandments dispels one of the pervasive myths about older films: that they were all in black and white, and that color did not happen until decades later. These scenes thankfully remain in tact, thanks to restoration done by the George Eastman Museum, which used DeMille’s personal 35mm copy as one of the sources.

It would be unfair to say that the second half of the film, which overstays its welcome, isn’t entertaining and engaging, despite how seemingly mundane it is. There are several sequences of note, worthy of the same praise given to those within the prologue. The destruction of the church near the end of the film is stunning, as is the scene in which Mary takes the elevator up to top of the Church’s roof. This part of The Ten Commandments is also elevated by its lead performances, especially Dix’s. He is so deeply charming and handsome as John; his unbuttoned vest and buttoned up shirt, sleeves rolled up to the forearms, could probably make anyone see the light and convert. Several actors in The Ten Commandments eventually made the leap to talkies, and Dix notably became a big-box office draw for RKO in the 1930s and was nominated for an Academy Award for his performance in 1931’s Cimarron. The performances are nuanced and natural, which might come as a shock to modern audiences who might still hold false beliefs about how acting in silent films was generally over the top and goofy. While it’s true that screen acting was still in its infancy in 1923, and some of it was over the top, a lot changed between when the first pictures were released and the filming of The Ten Commandments. In the early 1900s, the craft of screen acting evolved at lightning speed, becoming more naturalistic, and it’s wonderful to see a glimpse of that evolution in The Ten Commandments.

Will Hays was officially named head of the newly formed Motion Picture Producers and Distributors of America in 1922, and his primary job was to quell dissent among Hollywood’s critics when it came to censorship and the increasing moral ambiguity of its stars. In the early days of filmmaking, various censorship boards in the United States would cut anything and everything that did not meet societal standards of decency and propriety from films, so it is worth noting that the Paramount did not cut a single second of The Ten Commandments (per The House of Fradkin-stein). This is astonishing considering there is a frame in which Miram, Moses’ sister, gets her breast fondled in full view of the camera. It’s interesting that, while on the surface, The Ten Commandments is preoccupied with telling us a moral tale in showing the downfall of Dan McTavish, the film also shows a lot of decidedly ungodly things including murder, adultery, and greed in great detail. As author and professor William D. Romanowski pointed out, “A devout Episcopalian and Bible literalist, DeMille was also a consummate Hollywood showman with a keen sense of audience desires.” Known for baiting the censors, one has to wonder if DeMille was trying to have his cake and eat it too.

It is a miracle that The Ten Commandments survived past the early 1900s. As Eva Gordon explained in her biography of forgotten silent film star Theda Bara, no one really cared about preserving silent films (the earliest of which had become obsolete far before talkies arrived) until it was too late. By the 1930s, the fragile nitrate film stock was already disintegrating or bursting into flames. Fox Films, which later became 20th Century Fox, lost all of their silent films in a vault fire. But The Ten Commandments is one of the lucky ones. It prevails as one of the Hollywood’s most dazzling epics. Even today, it surpasses some modern blockbusters in technical and artistic achievement. The runtime may be bloated and the second half suffers because of its one-dimensional characters and uninspiring narrative, but The Ten Commandments remains one of the best spectacles in Hollywood history, a film that paved the way for a generation of epic storytelling to come.

Score: 21/24