Utter the name Stanley Kubrick to even the most casual of filmgoers and there’ll be a look of acknowledgement or even trepedation that is returned to you, such is the legendary director’s reputation for pushing boundaries and his overall impact on the film industry. The director of such monumental classics as A Clockwork Orange and The Shining, the American born but spiritually-British filmmaker, who passed away in 1999 just weeks before the release of his final film Eyes Wide Shut, left an indelible mark on Western cinema and has proven himself to be an inspiration to everyone from Christopher Nolan to Steven Spielberg over the course of such filmmakers’ reputable careers. This summer, at London’s architecturally sensational Design Museum, a peerless insight into the director’s career and artistic methods has been the centre-most exhibit on offer, filling the sizeable building’s ground floor from wall to wall with memorabilia, personal items and meticulously researched facts and figures to offer a truly fulfilling and inspiring experience to cinephiles young and old.

Stanley Kubrick: The Exhibition, which runs until 17th September, doesn’t simply open a door into the world of one of the greatest filmmakers to ever live, it invites you through an experience not indifferent to that of the famous Oscar-winning special effects scene of the filmmaker’s most indelible release 2001: A Space Odyssey, beckoning you through a mirrage of images from his films, each projected onto screens of different dimensions, raising your enjoyment the minute you walk through the entrance gate and fulfilling every expectation an avid museum-goer or film-lover could possibly expect thereafter.

Image by Ed Reeve (source).

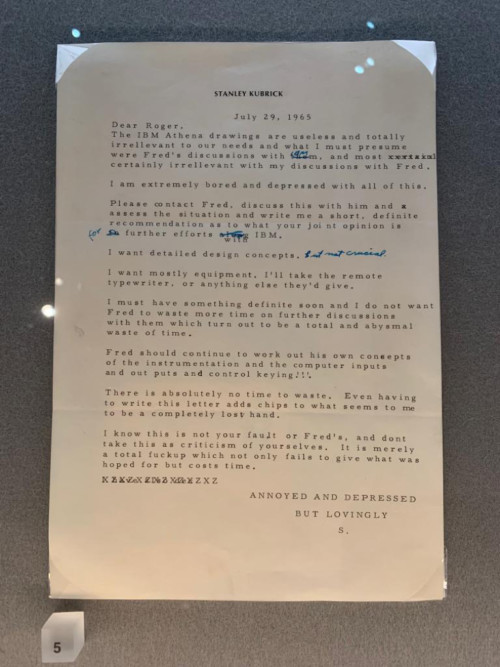

The most significant takeaway from the exhbition is the proof it offers of Kubrick’s incessant attention to detail and at times brash, and always very particular, communicative style. The director would spend years compiling notes and planning for the eventuality of filming, all of which is beautifully displayed in true-to-life book cases that are either trusty replicas or Kubrick’s actual items, and the effort he inputted to any given project was therefore expected of those he worked with, the many letters to and from creative partners acting as illustrators of his desire to get everything as perfect as he possibly could. Some such examples of this are the various editions of movie posters littered around the exhibition, each with notes from the director himself; pieces of history that not only illustrate Kubrick’s attention to detail but need for control over any given project from the ground up. Whereas modern filmmakers may leave the promotional material to that of the promotional experts (usually a third party company hired by the studio), Kubrick saw posters and other promotional materials as another way to present his story and as such exercised his right to get exactly what he wanted from the talent at his disposal. Font, font size and the way a poster was printed were just a few of the director’s notes on early editions of promotional artwork for The Shining, for example.

Recommended for you: Kubrick & Kids – The Work of a Dictatorial Director & His Child Stars

The director, apparently discontent with simply controlling the picture and the promotional material, apparently also liked to have a say regarding the translation of his movies, yet despite this almost obsessive level of control over meaning, he never sought for his viewers to see his movies as anything other than what they themselves saw them as, refusing to acknowledge widely held criticisms of how some of his films were provocative or even violence-inducing.

“The point I want to make is that the film has been accepted as a work of art, and no work of art has ever done social harm, though a great deal of social harm has been done by those who have sought to protect society against works of art they regarded as dangerous.”

The exhibition made a point of emphasising how his 1971 release A Clockwork Orange was used by politicians as a tool for fear, with one in the UK even calling for the ratings board to ban the movie altogether, while his 1957 war film Paths of Glory was banned in France (the country in which it was set) for over 20 years because of its negative representations of war and high ranking French officials.

Image: Jason Lithgo (Source)

Notes and letters to and from close friends or distant creative partners also expressed the director’s individualistic stances and specific methods of making films, one producer sending Kubrick a letter that insisted that those financing the film were growing concerned while in the same letter acknowledging how he was unlikely to get a response. The sense that Kubrick was almost reclusive in his research is something that rings strong through the exhibit’s many prized possessions, and there is a strong hint of sadness that accompanies the many personal and professional acquaintances that wrote to Kubrick with an expressed distance to the director. Kubrick, it seems from the vast evidence on show in this collection, was a figure not far from that of a loner, his one and only true passion being the cinema he had fallen in love with at a very young age and felt determined to better with his input.

It is precisely that which makes the exhibition so striking and memorable; the subject at its heart. Kubrick was a phenomenal filmmaker, yes, but he wasn’t born into the medium, he adopted it and asked himself “can I make a film this good?” Arguably the greatest director of all time would not have even entered the industry had he never seen a bad movie, and for all of his artistic knowledge and exceptional instincts for the medium, it was his hard work more than anything that made each of his projects so wonderful to watch and so interesting to investigate in this exhibition.

For Kubrick fans, this is a must-visit, must-investigate exhibition, but for fans of film in any sense, there is truly something to be learned, more to be acknowledged and so much to be inspired by. Stanley Kubrick: The Exhibition is simply unmissable.

Header Image: Ed Reeve (Source)

[DISPLAY_ULTIMATE_SOCIAL_ICONS]