Juste un mouvement/Just A Movement (2021)

Director: Vincent Meessen

“Cinema can serve to explore the creation of forms, their embryology.”

Jean-Luc Godard

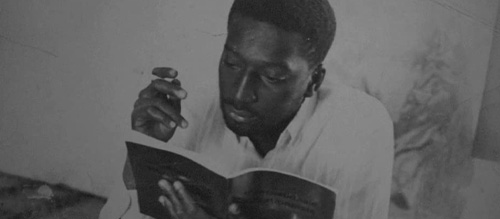

In 1967, French New Wave auteur Jean-Luc Godard (Breathless) released La Chinoise, a film about French university students studying Maoism, filmed in a cinéma vérité style that deliberately blurred the boundaries between film and reality. Senegalese artist and left-wing political activist Omar Blondin Diop played a small part in the film, took part in the May ’68 uprising as a student in France, and went on to be a major player in his home country’s widespread protests against French imperialism, before dying in prison in 1973 under suspicious circumstances. Director Vincent Meessen has taken a leaf or two out of Godard’s book in how he presents a documentary examining the life and times of Diop and his home country’s place in the world.

“It always moves me when I see cinema doing something different” muses Meessen after seeing a retrospective exhibition on Jean-Luc Godard. His film’s hook is something out of the True Crime genre – was Omar Blondin Diop’s death in prison an accident, a suicide, or an assassination? This plot thread soon falls by the wayside in favour of a broader political essay.

Meessen blurs the lines of reality from the beginning just as Godard would have done – staging reconstructions, leaving intact footage of himself interviewing Diop’s family, friends and fellow campaigners, including scenes of him giving actors instructions, even leaving in any outtakes or technical problems – each seemingly to comment on the artifice of documentary filmmaking itself.

The interviewees, the majority whom are family and friends of Diop telling the story of his life and political activity, are filmed in striking profile with Meessen’s camera occasionally drifting away to the side of the screen before the end of the conversation in order to bridge into the next scene. The in-depth, heartfelt discussion of Omar’s beliefs and his acts of rebellion in both France and Senegal from the accounts of those who knew him best, makes for powerful viewing.

Direct references to, and scenes from, La Chinoise are used throughout Juste un mouvement. At one point in possibly the documentary’s most meta scene, we see film of people watching a student film about Godard and La Chinoise within another film about one of the participants in La Chinoise. The two films have a lot in common thematically, examining left-wing thinking and how it could shape the world after drastic revolution, but much like was the case with Godard’s film, it’s the style, the metatextual, embryonic elements that end up getting in the way of, rather than enhancing, Juste un mouvement‘s message.

“When you’re a rebel, you don’t fight for yourself, you fight for a cause. What matters is that the cause prevails, that it triumphs, and not that you’re there to witness victory.” Diop of course did not live to see his cause, a true left-wing revolution, succeed.

Aside from Diop’s worldwide impact on the political stage and his ultimate fate, the film’s chief concern is the uncertainty of Senegalese national identity. Comparisons are made within the documentary between similar student protests in the late 1960s in France and those in China under Chairman Mao, and protests in Senegal in the same period.

If the planned violent protests against French President Pompidou’s state visit to the former French colony’s capital of Dakar had gone ahead as planned, lives may have been lost needlessly instead of the arrests that were made. Omar’s family were taken as political prisoners for their part in planning the protests that did occur, resulting in him abandoning his PHD studies to undergo military training and plan a kidnapping for the French ambassador to Senegal to force a trade. Though the plot was never put into action, Diop’s part in planning radical anti-government violence was enough to imprison him and lead to his eventual death.

“Our country is made up of two types of men: those who live within the orbit of Western Culture or those who are heading there, and those situated outside it.” Western plundering of African culture “has hindered the building of our identity. A people can’t construct itself without an understanding of its cultural heritage”. Even outside of France’s unwanted involvement in their country’s affairs, in more modern times China donated the Museum of Civilisations to Senegal, suggesting a different, more subtle kind of colonisation may still be in the country’s future yet.

Juste un mouvement has much to say about the legacy Omar Blondin Diop left on the world and the colonial legacy that has delayed development of Senegal’s distinct national identity (the latter of which could easily have made up an entire film), but Vincent Meessen’s sharp socio-political perceptiveness and his film’s raw emotional discussion is somewhat dulled by a busy stylisation and aspiration to follow in Jean-Luc Godard’s reality-blurring footsteps.

15/24