Directors: Joel Coen, Ethan Coen

Screenwriters: Joel Coen, Ethan Coen

Starring: William H Macy, Frances McDormand, Steve Buscemi, Peter Stormare, Harve Presnell, Kristin Rudrüd, Larry Brandenburg, John Carroll Lynch

The Coen Brothers famously claimed “This is a true story” before the main titles of their 1996 black comedy crime film Fargo. Many of the film’s viewers even bought this claim for a while – this small-town tall tale was so bizarre yet matter-of-fact and unsanitised it could only be real. This unquestioning belief of documentary and true-crime conventions became the whole premise for the 2014 oddball indie Kumiko, the Treasure Hunter, about a Japanese woman hunting for the money-filled suitcase that is seen buried in the snow in Fargo. Not long into the film’s shoot and not long after its release, the Coens admitted that this tall tale was entirely made up. This playful relationship with the truth is just one aspect of Fargo’s genius.

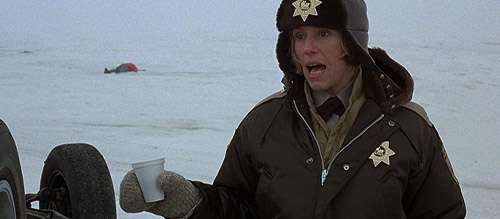

Car sales manager Jerry Lundegaard (William H Macy) is up to his eyeballs with money troubles, bad deals and fraud leaving him in unmanageable debt and with the very real prospect of a prison sentence on the horizon. In order to settle what is owed and buy himself a little comfort in one fell swoop, Jerry hires a pair of hitmen (Steve Buscemi and Peter Stormare) to kidnap his own wife (Kristin Rudrüd) with the understanding that they will split the ransom money put up by his wealthy father-in-law (Harve Presnell). But the plan begins to fall apart at the seams after the kidnapping results in the killing of witnesses and Police Chief Marge Gunderson (Frances McDormand) begins her investigation.

Fargo’s script is razor-sharp even by the Coen Brothers’ keenly-honed standards. Their verbiage and rhythms sound incredibly pleasing delivered in strong Minnesotan accents, which is understandable given the brothers grew up in a suburb of Minneapolis: “The little guy was kinda funny-lookin’” / “In what way?” / “I dunno… just funny-lookin’”.

Buscemi’s funny-lookin’ little guy hitman Carl is only nominally the brains of the operation, filling silences with inane chatter and regularly making a bad situation a whole lot worse as he does all the legwork for their kidnapping plot, all the while his psychotic partner Gaear chain-smokes and icily stares into the distance. “That’s a fountain of conversation there, buddy. That’s a geyser.”. The Coens love mismatched pairings of characters on circuitous journeys, and Carl and Gaear are a double-act for the ages, with such bad chemistry and clear loathing for each other’s personalities and working practices that you wonder how they ever teamed up.

There’s a twisted irony to Jerry wanting his kidnapping plan to be a “No mess-type deal” and later Marge commenting on the messy killing of bystanders on the side of the road as an “Execution-type deal”. Jerry is incredibly naive in conjunction with his sociopathic lack of feeling towards his wife Jean. In contrast, Marge is endlessly chipper and disarming considering her line of work, but she is under no illusion about the world she will shortly be bringing a child into – her warming and beaming smile falls into a sad frown as she is confronted by the very worst of humanity, whether they be armed with guns and power tools or a shit-eating grin and lies.

Jerry Lundegaard is one of the most despicable protagonists in film history. It’s the mundanity of his evil that is truly disturbing. He’s not a Walter White breaking bad for the good of his family, he’s in it for himself and to get out of the hole he has put himself in. He even forgets that his son might be adversely affected by the kidnapping of his own mother. The way the film is constructed with Gerry as the de-facto protagonist, the plot-driver – we are being asked to root for him to an extent, which is a bit of an ask – should be strange, but then again we are compelled time and time again by real monsters in true-crime documentaries, so this probably says more about us as a society than the Coen Brothers’ storytelling intent.

It’s the grounded gallows humour that really sells the “truth” of Fargo. Real people really can be this stupid when “a little bit of money” is involved, and no filmmakers know this – and write criminal stupidity – as well as the Coens. Look at Steve Buscemi in his garish red trousers, balaclava on and crowbar in hand, in broad daylight shading his eyes against the glare of the screen door of the Lundegaard house as Mrs Lundegaard watches him from inside in transfixed horror. Look at the witness clearing snow from his drive who saw and heard everything needed to convict the suspects, but who recounts the evidence in a roundabout Minnesota drawl in and amongst every other irrelevant detail of the conversation he had. Marge may be a hyper-competent cop, but she didn’t really need to employ top policing when it was only a matter of time before Jerry or Carl and Gaear made a big enough balls-up to give themselves away.

The Coens had their best and most frequent collaborators involved with Fargo. In addition to regular actors McDormand and Buscemi, there’s Roger Deakins in the third of his twelve times as the Coens’ cinematographer, and Carter Burwell in his sixth of sixteen times as composer, both helping to add atmosphere and richness to this grim-funny reality, a world just on the verge of the truth.

‘Fargo’ the series ended up adopting the same “This is a true story” tag as the film for each of its anthology seasons. Throughout Season 2 for instance, there are regular hints at odd goings on, before something extra-terrestrial shows up in the season’s penultimate episode then leaves just as suddenly. While the Coens’ film doesn’t go this far, it still calls into question the truth, or lack thereof, in film. No film, not even documentary features, can claim to be showing you the whole truth, only a version of it through editing. There are scenes in Fargo that don’t seem to go anywhere or seem to add anything to the wider picture, but that’s life, moments like this adding authenticity to fiction. Sometimes truth is stranger than fiction, and fiction masquerading as truth can be more funny-lookin’ than either.

23/24