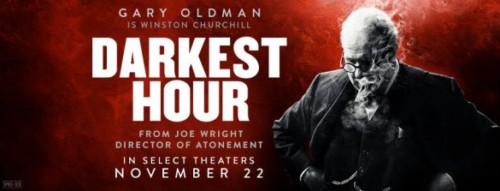

Darkest Hour (2018)

Director: Joe Wright

Screenwriter: Anthony McCarten

Starring: Gary Oldman, Stephen Dillane, Lily James, Ben Mendelsohn, Ronald Pickup, Kristin Scott Thomas

Joe Wright’s Darkest Hour, the tale of Winston Churchill’s fateful two weeks between becoming prime minister and overseeing the actions of Dunkirk, is a film plighted by obvious screenwriting techniques, distracting visual choices and a nostalgia for a time where upper class aristocrats were so anti-Europe and pro-war that only in 2018 could a film such as this have been made. Yet, in centring all of this right-wing, pro-brexit nonsense on an utterly astounding performance from Gary Oldman, Darkest Hour actually manages to manufacture a humane and almost likeable portrayal of a historical figure as problematic as the war itself; a career high point for an actor with an already existing range of top quality work under his belt. This 2018 release, and its many Britishisms, may be ideologically opposed to much of what is widely deemed as reasonable and acceptable in the 21st century, but it’s got some bloody good acting in it!

Darkest Hour is the sort of film where the upper class, historically important figure is introduced to a number of less powerful and wealthy cohorts along [usually] his journey in order to discover that those with less than himself can sometimes be of use, so long as he can take credit for it. It’s the sort of film that tries to diffuse the problematic idea of presenting a character so divisive as Churchill as entirely good that it works very hard to show him making questionable decisions, the collection of which only come to reinforce the very stature of his greatness. Darkest Hour is basically the sort of film that updates Facebook 5 times a day about the amazing work it’s doing by helping out impoverished Africans on a poverty holiday, or takes a picture for Instagram when it gives money to a homeless person.

At no point in the film is this more evident than in a brief moment of rebellion from the war-time Prime Minister which sees him instinctively exit his previously arranged private car to go and “be a part of the world” on the London underground; a sequence in which he takes in the thoughts of the public, including some of a black man seemingly exempt from the horrendous treatment that people of his race suffered at the time. He takes what he considers to be a public consensus (of a train carriage of Londoners) in order to decide the future of many of Europe’s armed forces, and Darkest Hour celebrates this as Churchill learning to be a “man of the people”, a spiritual guardian for all men, women and children. For the first time in his life, he rides public transport, and that makes him good, because only good men would lessen themselves to such fodder. It’s the sort of rebellious act that would put even Mrs. Theresa May Prime Minister to shame. Surely the tube’s more dirty than a wheat field, too?

Infuriatingly simplistic and often reductive attempts to humanise the man like this are scattered throughout the film, seemingly inserted as a means of appealing to the working class pro-brexiteers that would likely embrace a celebration of someone so patriotic. It’s a quite insulting attempt to garner empathy for the former Prime Minister that is about as well disguised as Gary Oldman’s fake double chin, and it acts only to reinforce the cinematic fable that poverty is a place worth vacationing to if you have the safety of your higher social standing to fall back upon (see Titanic, among others). The major issue as regards the script’s very nature is that this is a film about a historically important politician that doesn’t try to honestly explore his personal or political flaws and weaknesses, alongside his strengths, but instead tries to paintbrush history so that no personal or political critique is offered at all, birthing a film that is not only lacking in terms of honesty and quality, but is also therefore entirely in the hands of its own ideological beliefs, those of which are largely pro-war and anti-European.

Politics aside, the screenplay – particularly the dialogue – is just as infuriating from a cinematic perspective as it’s laced with obvious nods to history in a manner which is altogether unnatural in terms of how people would usually be heard as interacting with one another. We know that Churchill was to blame for the Bengal Famine in India because someone blatantly says he was responsible for the deaths of 10,000 people. We know that former Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain has cancer because he says “I have cancer”. It’s like McCarten – whose screenplay for The Theory of Everything was excellent – was attempting to show off as much of his historical knowledge as he possibly could in the script itself, and he therefore lessened the impact of what is a fascinating and culturally significant story because it meant that the film became as false in its dialogue as it was in its presentation of the truth via awful story beats like that of the tube interactions referenced earlier. Ultimately, these were wounds the other elements of the film could not heal, despite some positives.

One such a positive was the level of performance on offer from the entire cast, but particularly from Gary Oldman. The now legendary British actor, whose 30 plus years in the industry have seen him fill a number of iconic roles, was outstanding as Churchill in this film, offering not only a transformative performance but also one of subtlety and tenderness. Oldman presented the former primeminister as almost childishly unguarded, telling with his eyes an innocence and deep-rooted goodness that the character’s scripted (and historical) actions may not have always suggested. Churchill, through Oldman, became vulnerable as well as powerful, and the impact that this had on the film overall was quite astonishing.

Make no mistake that Darkest Hour is absolutely indebted to the work that Oldman put into this film, for his performance was not only fascinating in the ways already referenced, but it was lifting in terms of how the film will come to be seen, as it was through his astonishing performance that the film was given humanity, that Churchill became a source for empathy, that the threat of war and overall conflict was most prominent.

Joe Wright must also be commended for his dedication to ensuring the camera remained focused on Churchill’s (therefore Oldman’s) journey throughout the picture, as the choice to do so did become a saving grace for a film falling down around the two of them. Visually, there were many sequences that seemed to over-complicate the approach for aesthetic reasons but not for any meaningful reasons – such as long, tracking shots which are now a famous part of Wright’s arsenal following his famed Dunkirk beach scene in Atonement – the likes of which felt heavy, unnecessary and distracting in the case of Darkest Hour. The title cards were also almost unnecessarily modernistic and huge, becoming similarly as distracting from the realities we were apparently witnessing. Visually, the film simply felt removed from the severity of the war, but in focusing so intently on the Churchill character, the visual journey did bring the weight of the character’s decisions into prominence. The acts of the Prime Minister (and the way in which such acts were portrayed) did therefore hold a sense of gravity for the film to form itself around.

The work in the edit was absolutely reinforcing of this positive aspect in that it not only emphasised the focus on Churchill but it gifted the film a rhythm that steadily chugged away until hitting its crescendo at the story’s climactic moments (often speeches). In this regard, the film was all but faultless, and together with the fantastic performance of Gary Oldman, and a supporting turn from Lily James that was also powerful though in a much quieter way, helped to build empathy that was otherwise absent from the picture.

Conclusively however, Darkest Hour wasn’t a sensational movie, though aspects of it certainly were. At its base, there wasn’t much to write home about, but given its decoration – directorial choices, the editing and most importantly the performances – there seems to have been born a movie that transcends its problematic politics to become a watchable biopic. This is certainly not a film you’d necessarily associate with 9 BAFTA nominations and 6 Oscar nominations, but Gary Oldman’s performance is certainly a worthy contender for Best Actor.

Darkest Hour will be remembered for being an actor’s movie, so if you like strong, grandiose performances you’ll enjoy this film a little more than someone more interested in the other aspects of filmmaking, but it’s unlikely you’ll remember this as a classic either way.

14/24

[DISPLAY_ULTIMATE_SOCIAL_ICONS]