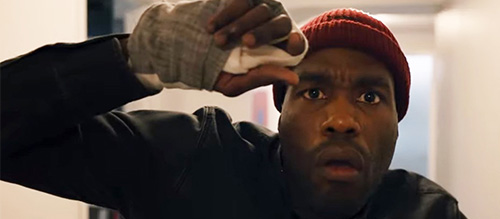

Candyman (2021)

Director: Nia DaCosta

Screenwriters: Jordan Peele, Win Rosenfeld, Nia DaCosta

Starring: Yahya Abdul-Mateen II, Teyonah Parris, Nathan Stewart-Jarrett, Colman Domingo, Tony Todd, Virginia Madsen, Vanessa Williams

A Candyman movie produced and co-written by Get Out and Us filmmaker Jordan Peele seemed on paper to be a dream pairing. In all honesty, nobody wanted anyone to touch the iconic Candyman lore, but if someone had to, Peele was the one to give it a damn good go. Here he presents Nia DaCosta’s sequel to the original Candyman film from 1992 (itself based on Clive Barker’s short story “The Forbidden”) which follows Anthony McCoy (played by Yahya Abdul-Mateen II), a young artist who discovers the Candyman legend when looking for new inspiration for his art. Heading to Cabrini Green, site of the legend and the events of Helen Lyle’s murder spree thirty years before, the spirit of Candyman begins to manifest itself around Anthony, and a new wave of terror unfolds.

Urban legends are what become of a collective’s conscious and unconscious fears and troubles, manifesting in morality tales. The fast-flowing river becomes translated into a monster that lurks in the depths, waiting to snare unsuspecting children who sneak off against their parents’ warnings. Carbon monoxide poisoning in traditional South African households with a central smoke stack ends up as the monstrous Tokoloshe. Decades of violence, poverty, and crime as a result of racial inequality and neglect in Cabrini Green become the legend of a hook-handed man in the mirror, the Candyman himself. These myths and legends arise naturally, and are almost impossible to trace to a singular source. They’re socially organic in nature. Stories get passed by word of mouth, generation to generation, evolving over time like Chinese whispers. Hence the irony in watching this rebooting of a franchise about such an organic urban legend which feels so incredibly manufactured…

The main issue with Candyman (2021) is the script. The actors perform their roles admirably, and DaCosta’s direction, for all of its Kubrickian elements (even replicating the extreme low angle of Jack Nicholson up against the storeroom door in The Shining with Abdul-Mateen II furiously painting), is controlled and purposeful in its own unique way (though there are issues which shall be returned to). The production design is good, and the music isn’t awful (though it is incredibly droning and bland, and cuts out Philip Glass’s iconic “Music Box” theme until a clichéd ‘creepy’ rendering for the credits). The cinematography works for the film, never going too over-the-top (although someone should have mentioned to cinematographer John Guleserian that in a particular sequence under a church near the end, we can’t even see the minimal amount of stuff we’re meant to be able to), and the Lotte Reiniger-style animations are a fun touch. Everything on a filmic level works, just about. They do their jobs. But the script is ungainly in its feel and flow, resorting to the beats of a routine slasher with a mental-illness surrogate thrown in to make it “of-the-times” and in the new age. Whereas the original film was a complete fever dream, unique in its setup, its presentation, its villain, and with a refined elegance and grace even in its most horrifying and graphic moments, Candyman (2021) finds itself a teen flick trying on its dad’s suit for the first time, like three kids stacked in a trench coat. Instead of allowing the story to flow naturally in new and inventive directions, the narrative is pushed in directions the writers felt were needed in order to get their points across, using cliché and caricature on occasion to do so. The most inventive part is the mirror-like reversal of the production company names in the logos presented before the film even starts.

As a result of all this, certain character motivations end up ridiculous, the interesting blurring between protagonist and antagonist is badly handled, and the final moments come messily before the film just ends. The twists are annoyingly dull (even having twists is frustrating, as if the film is trying to be too smart for its own good), and even an appearance by Tony Todd is wasted by the atrocious ending seconds of the film. Candyman’s end is so abrupt that you’d be forgiven for verbally shouting ‘wait, is that the end?’ Everything about this sequel is a marketable studio commodity, and it is so much worse for it.

Candyman ends up coming off as pretentious instead of poised. Coming back to DaCosta, she shies away from much of the actual violence in the film, going for suggestion rather than anything too explicit. This is fine in some moments, but occasionally you need to feel some brutality behind something brutal. There’s too much planning and thought behind the intellectual appreciation of the film, and the emotional impact falls by the wayside. A film shouldn’t spoon-feed you everything; the ‘what you don’t see is scarier’ philosophy works very well in many cases (the swimming pool death in Let the Right One In springs to mind), but sometimes you need a gut-punch to shock people into paying attention. Additionally, critics may praise the “social commentary” (a term reserved for first year film students who haven’t yet learned to do away with such a meaningless phrase. After all, what film doesn’t, in some way, comment on society?) but themes and messages mean nothing if the medium you’re using to carry them feels stale and uninspired.

Early in the film, at a display for the new works of local artists, Anthony explains the deep meanings behind his art display to a critic, rambling on about the deep connections between his display’s style and theme and social relevance and form and all that good stuff, but the critic really doesn’t give a damn. She isn’t feeling anything. Candyman isn’t that bad, but the scene still seems to capture the essence of the film’s biggest issue: it’s incredibly intelligent, but ultimately lifeless, leaving us with an empty candy wrapper complete with a list of all the ingredients to a candy we can never have.

13/24